8 Best UX Persona Examples from Real Companies and How to Create Them

Khanh Linh Le

Created on Nov 25, 2025

Have you ever created a persona that nobody on your team can eventually use? If the answer is yes, you're not alone. In a survey of 203 UX practitioners, about one-third said their personas were “rarely” or “never” used.

And from my experience, it usually comes down to the same blind spot: we built the persona from assumptions instead of real behavior. That makes it read like a story, not a design tool.

So, in this piece, I’ll walk through eight real-world persona examples, explain why each one works (or doesn’t). I'll also include a simple, research-first process you can follow to create more practical UX personas.

What is a UX persona?

A UX persona is a profile of your ideal user. It’s fictional, but based on real data like age, job, habits, goals, and frustrations. You can think of it as a tool to help you make design decisions that matter to your users.

You might love building UX personas or think they’re useless. I get it. Some teams swear by them because they make prioritizing features, designing flows, and writing content way easier. Others skip them, saying they’re just templates that don’t capture real behavior.

But here’s the thing: a good persona isn’t about filling in boxes. It includes all the information that affects design, like motivations, tech comfort, pain points, routines, and channels your user prefers.

When you make it relatable, your team can look at it and immediately know who they are designing for.

Image source: Nourah Alhassan

So how can you create user personas like that? Let's break down some of the real-world personas below for inspiration.

8 UX persona examples

Seeing a UX persona in action makes it way easier to understand the persona design process.

In this section, I’ll share 8 real-world examples from companies that use personas to guide buiding decisions.

1. Mailchimp

Mailchimp’s 2013 persona work gives you a great look at how a small team can create something genuinely useful without layers of process.

One of their key qualitative personas was Fred, the “ideal user.” He came from interviews with internal stakeholders who had strong opinions about who they thought the user was.

But when the team compared that belief with data from user research, they saw a gap. Fred then became the anchor persona that clarified Mailchimp’s direction: build a product that feels powerful but doesn’t overwhelm people running small businesses or doing marketing on the side.

They also created four other archetypes: Andre (developer), Eliza (PR manager), Ada (receptionist), and Mario (studio consultant) to reflect different workflows and challenges.

These personas make sense for the product Mailchimp was offering at the time. In 2013, they were still growing quickly, so they didn’t need a dozen hyper-segmented personas. They needed someone who represented the type of user they wanted to serve best, even as the product evolved.

If you’re early-stage, you can take the same approach. Start with a simple, aspirational persona, such as Fred, and refine it as your real users become clearer. Even something as simple as what Mailchimp did here works:

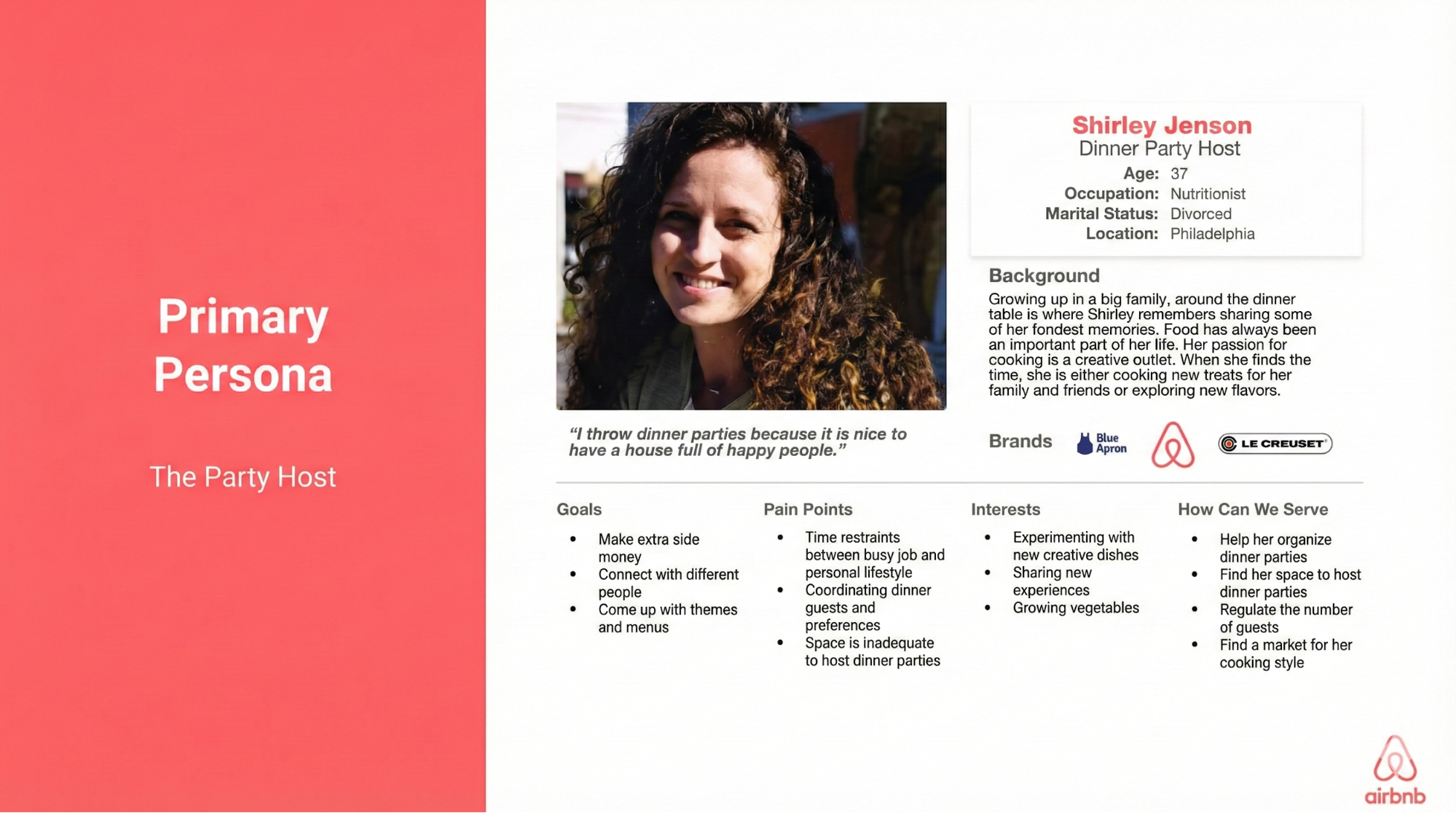

2. AirBnB

Airbnb’s persona, Shirley, the “Dinner Party Host,” is a great example of a persona built around target user's perspective: people who love hosting. Airbnb didn’t start with demographics here. They started with a deeper insight, the emotional payoff hosting provides.

When I looked through this project, what clicked for me was how Airbnb zoomed in on hosting as an identity, not a task.

Shirley throws dinner parties, obsesses over details, and wants guests to feel taken care of. That mindset gives Airbnb a clear design direction: make the product feel like a partner in hosting, not just a booking platform.

And you can see how her pain points naturally steer product thinking. She worries about prep time, making the experience consistent, and juggling small logistics. These are all the problems Airbnb can genuinely help solve through templates, host tips, smarter scheduling, and experience-sharing between hosts.

If you’re building a marketplace or community-driven product, a persona like Shirley helps you design around both functional and emotional needs.

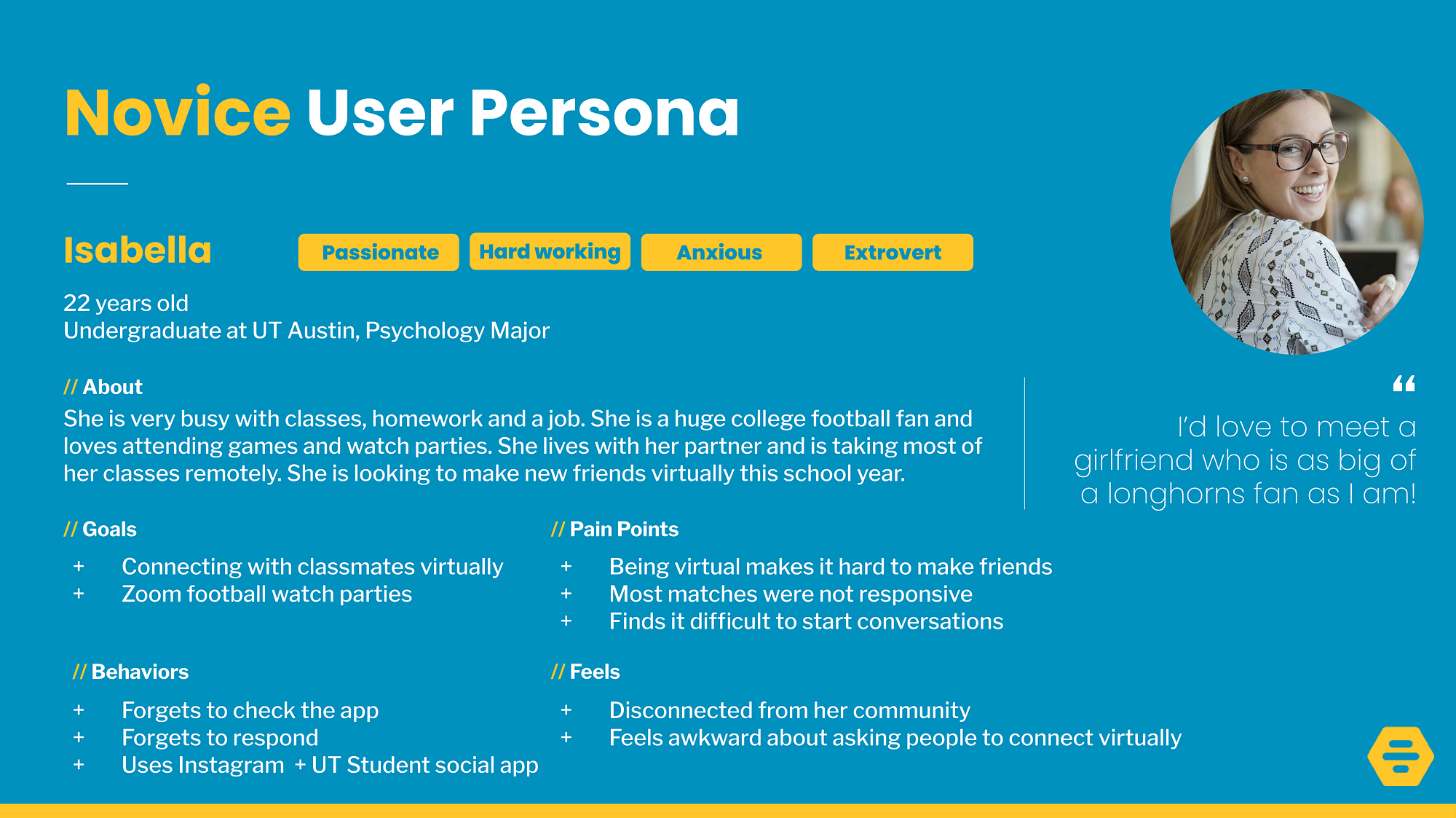

3. Bumble BFF

What struck me about this Bumble BFF case study is how the designer didn’t invent personas from thin air.

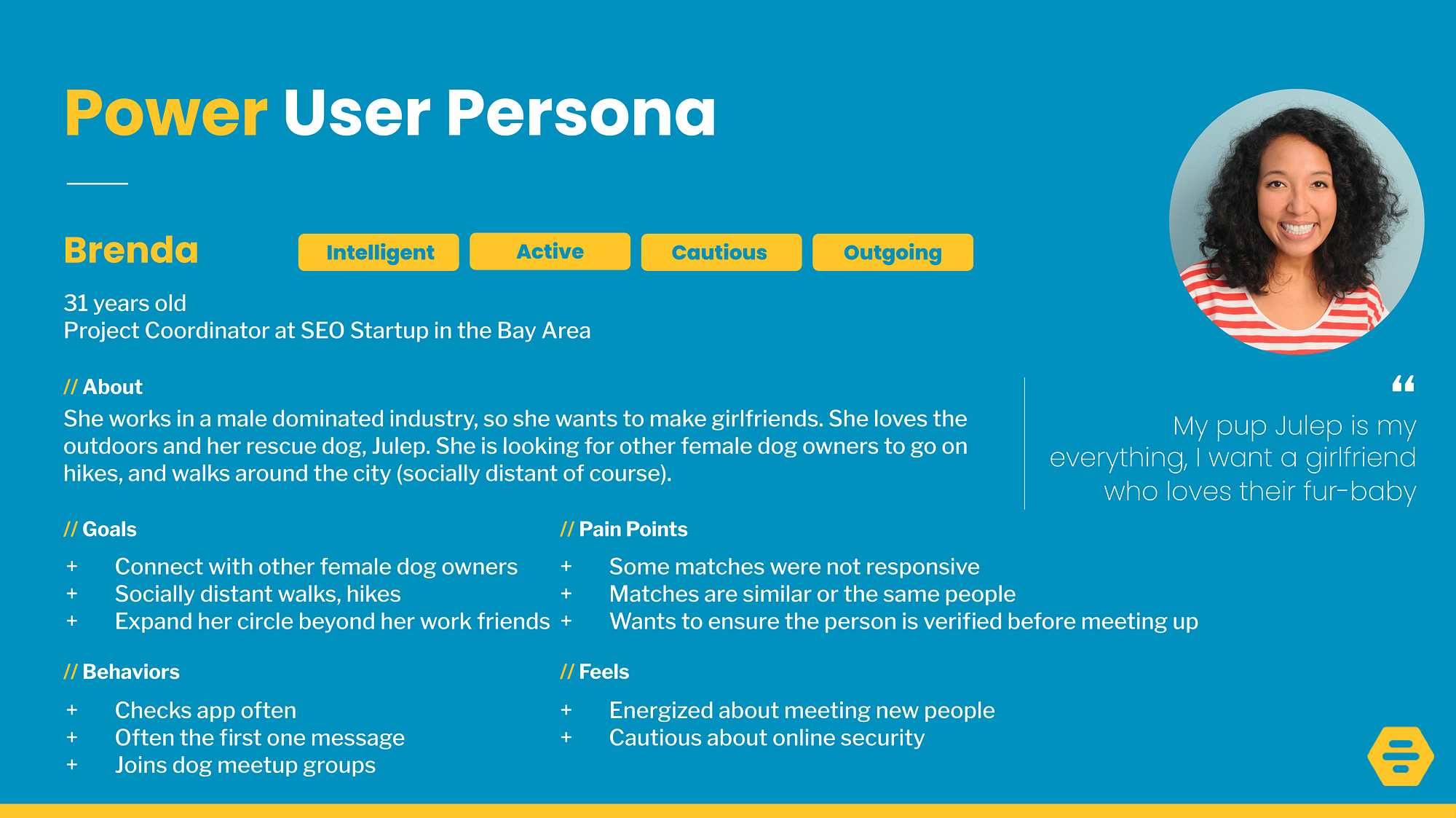

The pandemic reshaped how people socialize, so the team paid attention to the emotional patterns shaping user behavior. That’s how two distinct personas emerged: Isabella (novice user) and Brenda (power user).

If you look closely, Isabella exists because many users were joining BFF out of situational loneliness. Think relocation, isolation, or losing existing social circles. She’s open-minded but hesitant, and that hesitation affects how she uses the app.

Brenda, meanwhile, represents the other extreme: someone who already cracked the “friend-making code.” She’s using BFF regularly, has formed real friendships, and expects the app to keep up with her social rhythm. Her behavior tells the team where the product already succeeds.

Nevertheless, the tension between these two personas revealed a key friction point: both groups felt awkward discussing COVID safety. That insight directly shaped the “hangout preferences” feature. Without those personas, this pain point would’ve stayed invisible.

This is the kind of persona work that helps improve a product because it explains what’s getting in their way.

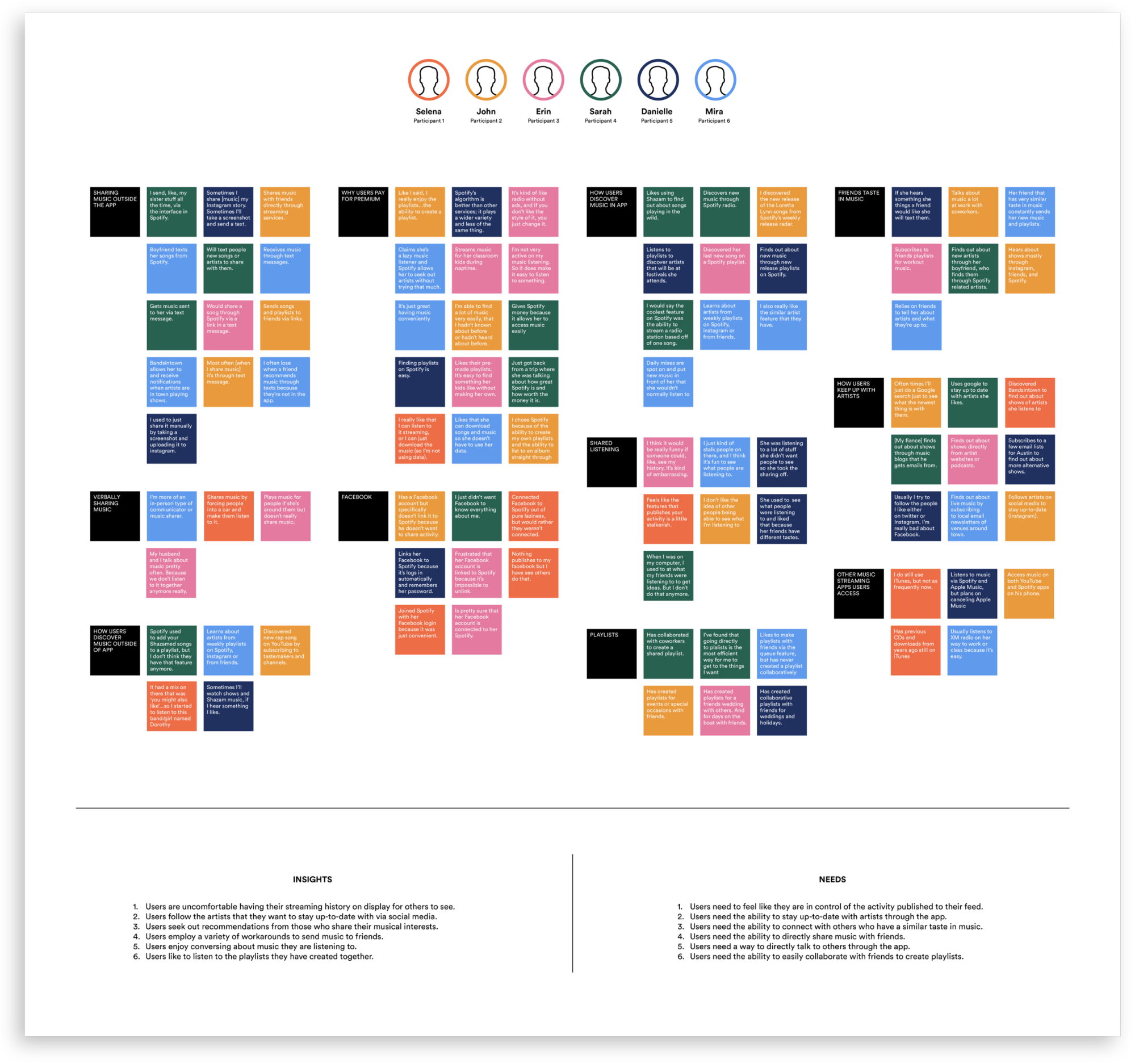

4. Spotify

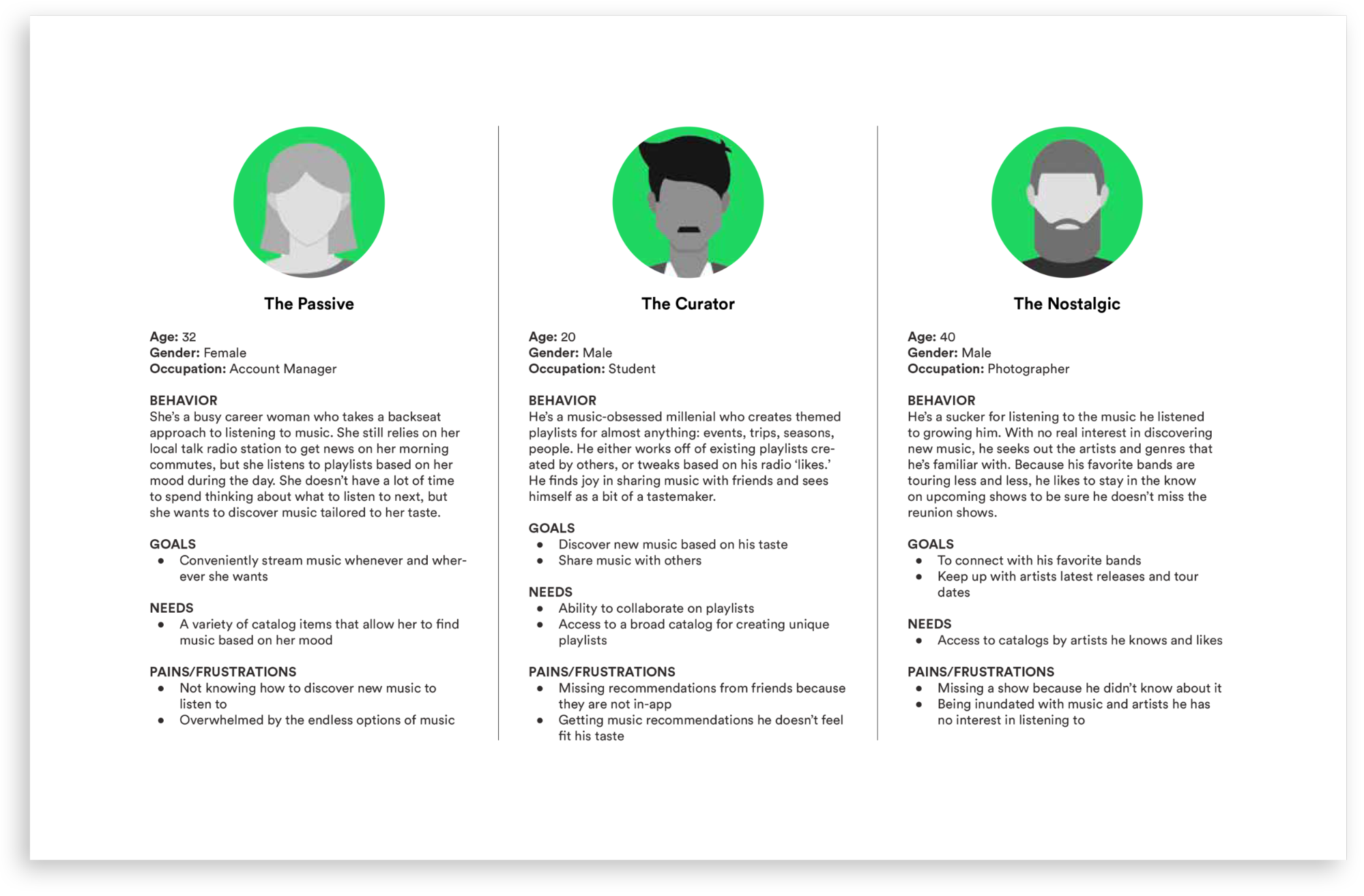

Spotify’s persona project clicked for me because it was about fixing a strategic disconnect.

Different teams at Spotify were optimizing for different outcomes, and nobody had a shared definition of who they were building for. When that happens, product decisions get fuzzy fast.

Therefore, instead of creating personas based on surface-level things like genre preferences or age groups, Spotify went deeper.

They ran diary studies and contextual interviews to understand the role music plays in people’s lives. That’s how they uncovered patterns like “togetherness-driven listening”, which eventually shaped personas such as Shelley.

Shelley isn’t interesting because of her demographics. She’s interesting because she listens in ways analytics can’t explain. She uses music as a social tool, for family time, household routines, and shared moments.

Once you see this behavior, features like collaborative playlists and smooth handoff between devices suddenly make perfect sense.

What I appreciate most is how Spotify operationalized these personas. They built an internal site, ran workshops, and turned the personas into a real decision-making language. That’s the whole point: A persona only matters if it helps you choose what not to build.

5. Webflow

Webflow had an interesting approach when it came to building their first UX persona ever. Webflow’s founding team worked out their first one around Sergie, co-founder and freelance designer, because he was their user.

By starting with Sergie, Webflow locked in laser focus on the pain point many designers felt but didn’t talk about, which is the tedious handoff to developers. Rather than try to serve everyone (like Wix or Squarespace did), they aimed for designers who needed both creativity and control.

I think that’s a masterstroke. It gave them a real “beachhead”, a user profile who was both deeply frustrated and deeply invested. Instead of trying to scale from the start, they doubled down on this one persona, aligned their roadmap around that, then expanded to other user types later.

For you, if you’re building a product in a crowded field: Pick the hardest, most valuable user, and design for them first. The clarity might just be what helps you outpace the giants.

6. Nextdoor

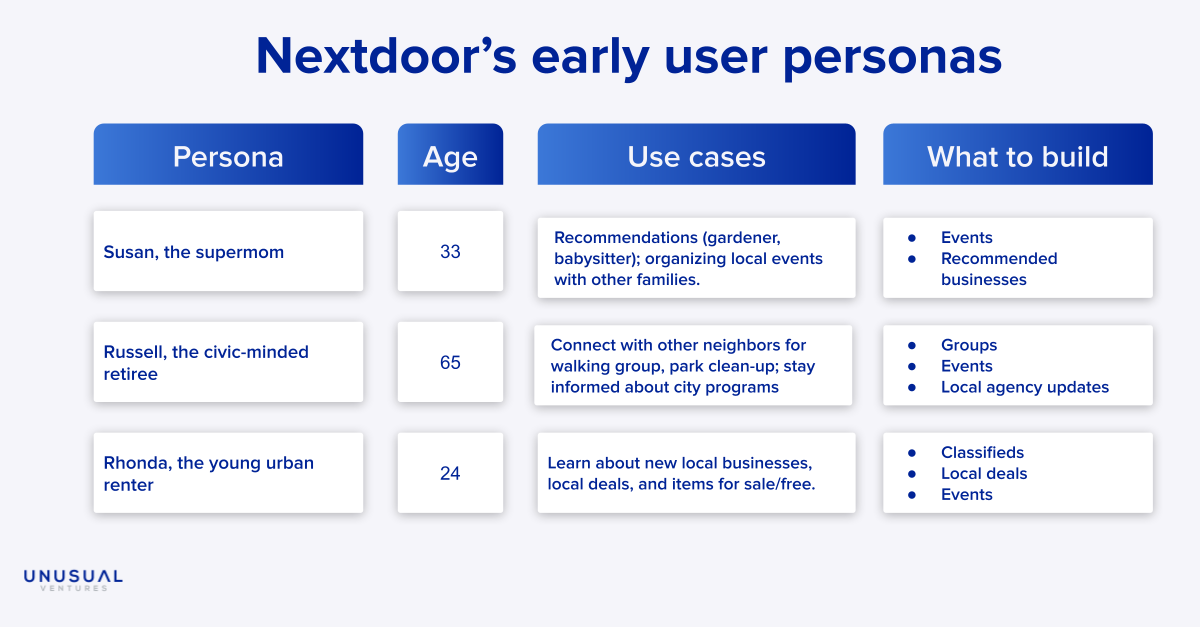

Nextdoor is one of the few companies where the persona was the backbone of their entire go-to-market strategy.

They didn’t chase “typical users” at all. They chased a Founding Member persona: someone who takes initiative, cares about their neighborhood, and wants to bring people together. They are people who applied to start their own Nextdoor “hood,” and the Nextdoor team collected stories about why they wanted to do that.

Here’s the logic: if you recruit the right people to kick off a community, they’ll invite others, evangelize, and set the cultural tone. Nextdoor didn’t just guess who those people were; they used applications, user interviews, and surveys to validate their traits.

What’s clever is how this persona transformed their product and the go-to-market strategy.

Because Nextdoor is laser-focused on early adopters who care about managing their neighborhood, they could build features and messaging around trust, local relevance, and shared accountability. That alignment meant they were building an infrastructure for the community.

I think this is a great lesson for any product that relies on network effects. Sometimes your most important persona is the user who kickstarts everyone else’s experience.

7. Hubspot

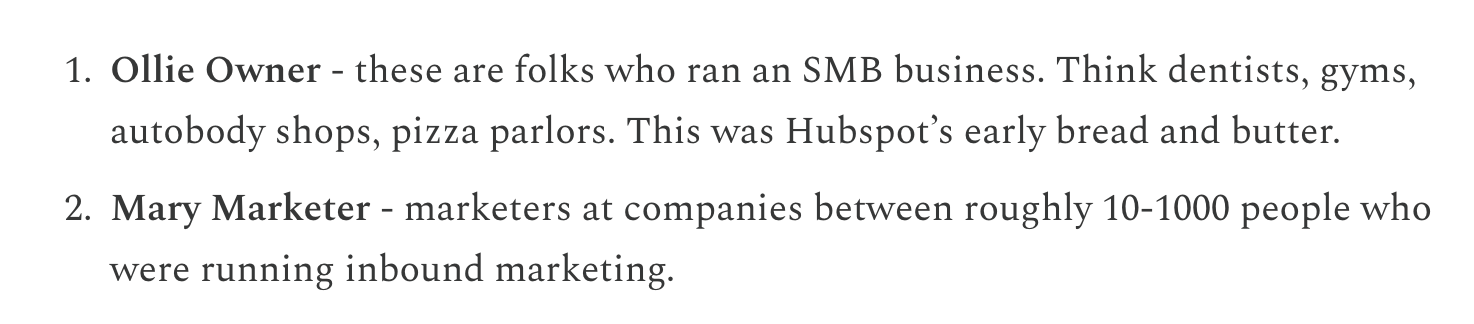

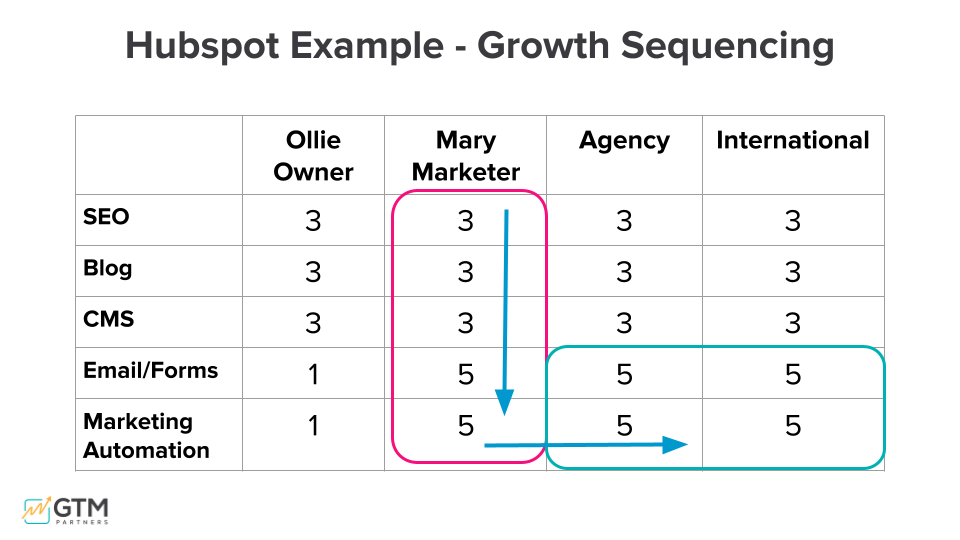

HubSpot’s early persona work is one of the clearest examples of how the right persona can shape a company’s entire trajectory.

In 2010, they were sitting at $15.6M in revenue. However, retention was shaky, and customers weren’t using enough of the product.

When I dug into their story, I realized their biggest turning point came from understanding two very different types of target audience: Ollie Owner and Mary Marketer.

Both personas liked HubSpot’s early blogging and CMS tools. But liking and loving are not the same. Neither persona saw those features as irreplaceable, which meant HubSpot wasn’t building around a true 5-out-of-5 need yet.

That changed the moment they introduced integrated forms. Mary Marketer’s workflow flipped overnight. Leads flowing directly into Salesforce were life-changing. She scored it a 5. Ollie Owner? He barely noticed. A clean 1.

That split forced a hard question: chase Ollie or double down on Mary? Choosing Mary turned out to be the billion-dollar call. It pushed HubSpot toward marketing automation, agency expansion, and eventually the multi-product ecosystem you see today.

This is why the persona creation process matters. When you know who loves your product, your roadmap stops guessing and starts compounding.

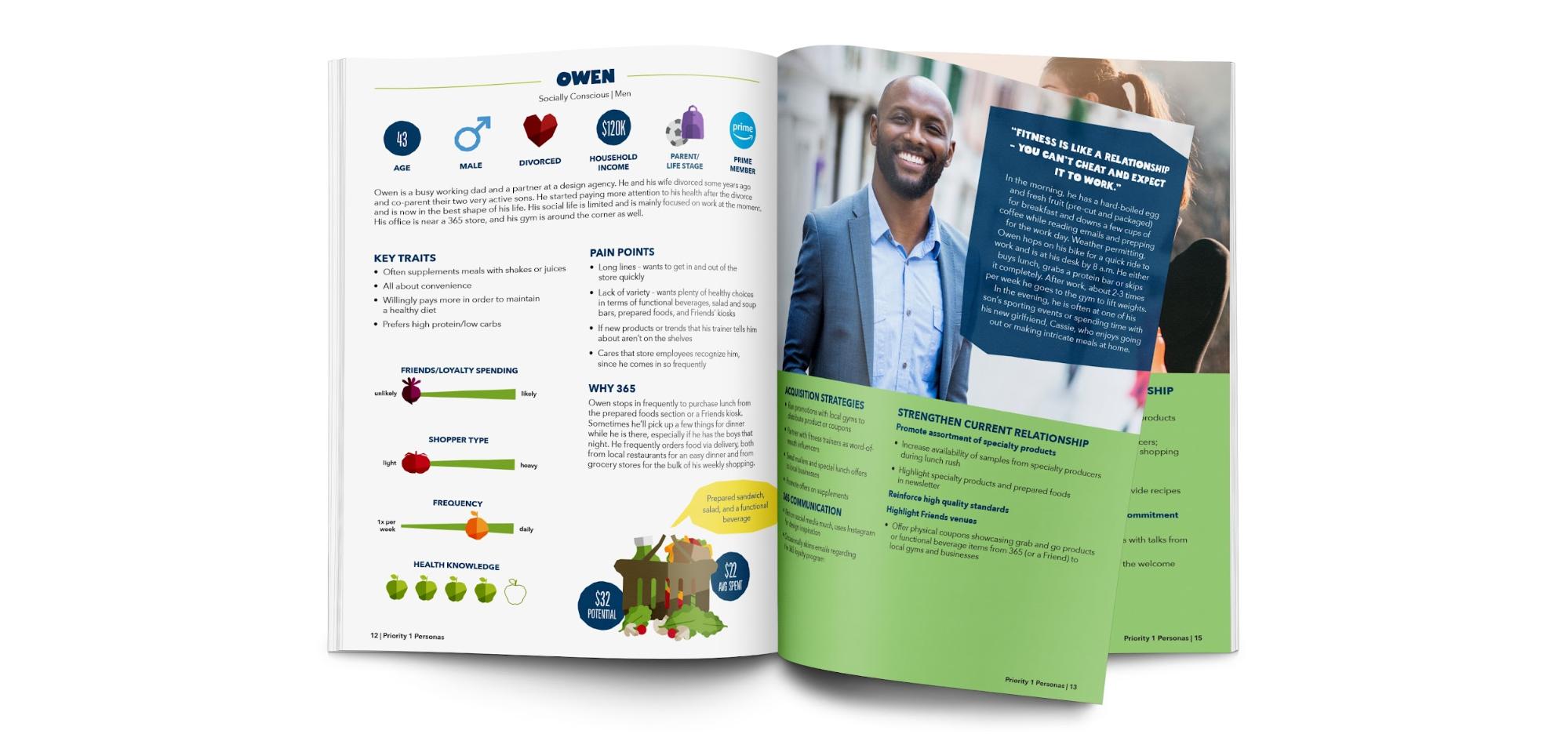

8. Whole Foods

Whole Foods Market set up its 365 brand to offer lower-cost, organic-friendly groceries. But after a couple of stores, their marketing team realized they had tons of data and very little clarity about who their real customers were.

So they went all-in on getting insights from their existing user persona data. Instead of assuming their typical shopper was simply “a millennial who wants affordable, healthy food,” they ran deeper customer clustering.

And that’s when an interesting insight surfaced.

Even within their millennial user groups, there wasn’t one type of customer at all. There were multiple personas, each with different motivations, shopping triggers, and definitions of “value.”

One of the statistical personas that emerged from this data is Owen, a busy, health-conscious dad who values convenience over everything else. He buys high-protein meals, pays more for healthier options, and shops frequently because it fits his routine.

I like this persona because it tells you his spending habits. You can immediately see how this helps a grocery brand like Whole Foods 365. If your user is motivated by “healthy but affordable exploration,” you rethink shelf layouts, sampling events, and even how you write product labels.

The lesson here is simple: even when you have mountains of data, building user segments using broad labels like age or demographics is a fast track to stereotypes.

How to create a UX persona: 5 tips and best practices

When you sit down to build a UX persona, your goal should be more than just pretty user profiles. It should be something that drives real design decisions.

Research shows that personas aren’t just fluff: In controlled experiments, teams using them created designs with better usability and stronger user alignment.

So let’s break down how you can create UX personas that feel real, stay useful, and support your product choices.

1. Identify your most important users

Before you interview anyone or sketch a single persona, you need to know who you’re trying to understand. This step sounds obvious, but it’s where most teams accidentally drift as they collect insights from whoever is easiest to reach instead of the users who actually matter.

Your “most important users” will depend on your company’s maturity:

-

If you’re established, that might mean the people driving the most revenue or using your product the most.

-

If you’re early-stage, it might mean the ideal users you want to attract.

And to do that, you need to screen deliberately. Market segmentation research gives you a starting framework, but I’d go further. If you already have a user base, pull whatever data you can. Think demographics, usage patterns, retention cohorts, even simple survey responses. These signals help you spot patterns worth exploring.

If you’re new and don’t have users yet, you can borrow insight from the market. Spotify did this early on by studying listener habits across regions and competitor apps to map who they should design for first.

Once you’ve collected enough directional data, create provisional personas.

These aren’t final. They’re placeholders that help you decide if you still need to conduct user interviews or who to interview next. It ensures you’re talking to people who reflect the behaviors you care about.

Think of them as hypotheses you’ll refine through real conversations.

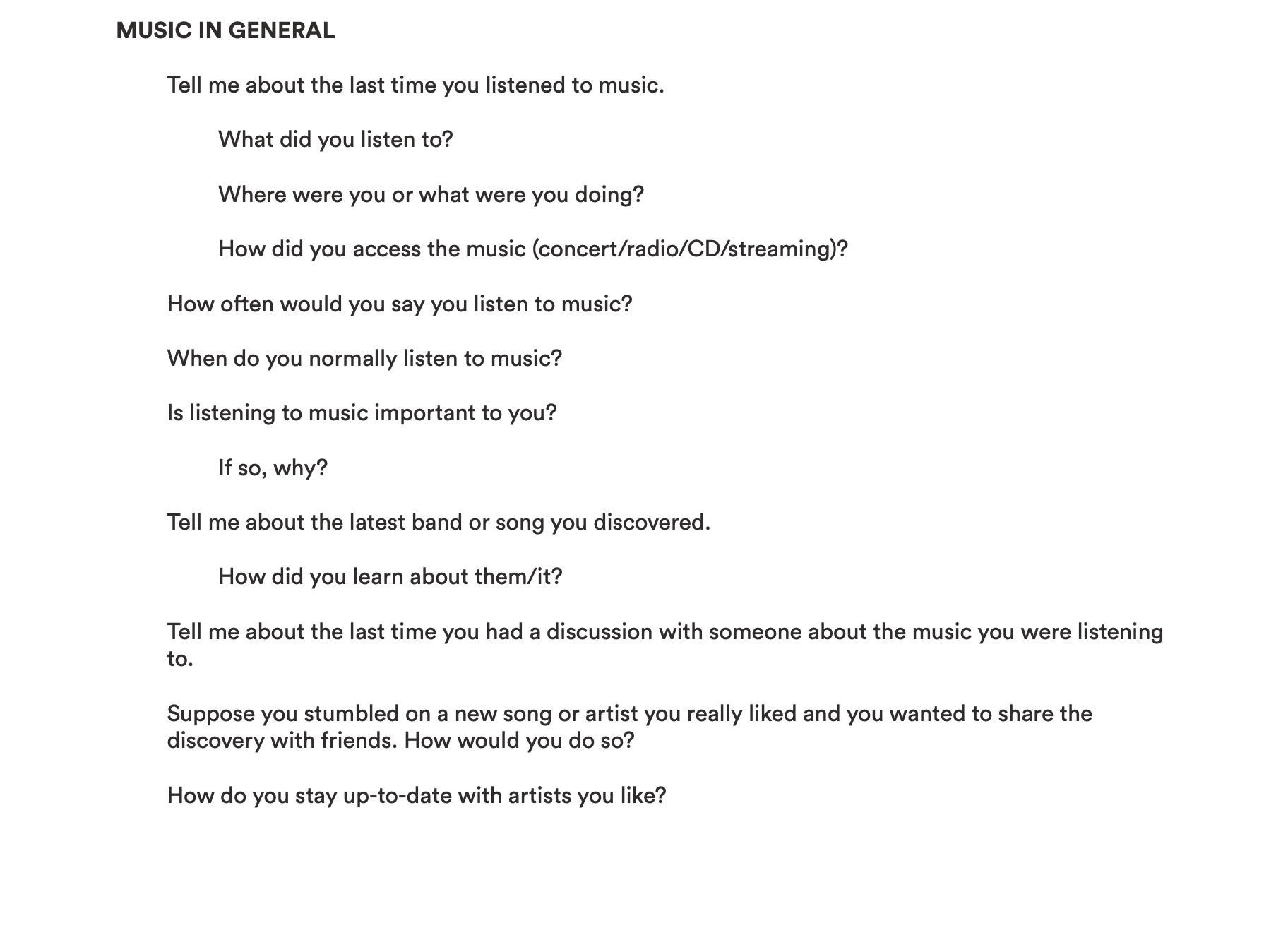

2. Pick a list of questions to ask

Once you know who you need to learn from, the next challenge is figuring out what to ask them. Interviews and observation are your two most powerful tools here, but they only work if you collect comparable, meaningful data.

That’s why you need a clear interview script or research protocol. It helps you avoid improvising your way into irrelevant conversations and ensures every participant gives you insights you can later compare.

When I build these guides, I always start with the gaps:

-

What does the team not understand?

-

What details would meaningfully influence design decisions?

-

What has sparked internal debate?

Those are the areas where your questions should go first.

The Spotify team did this well. Their interview guide dug into listening habits, sharing routines, emotional context, and device usage. These are things that directly shape how people experience music.

You can use a similar structure: open-ended questions, prompts for stories, and requests for real examples instead of hypotheticals. People reveal far more when they show you how they behave than when they explain what they think they do.

And whenever possible, talk to participants in person and in context. Seeing someone use your product (or a competitor’s) in their natural environment gives you details no survey can match.

Keep interviewing people in each role or segment until patterns start emerging. If you need help defining segments or screening participants, tools like HubSpot’s Make My Persona generator can give you a quick starting point.

3. Analyze your data to identify patterns

Most teams get stuck here because there’s so much data like notes, quotes, screenshots, and observations that it feels messy. The trick is to zoom in first then zoom out.

Before you look for patterns across all users, make sure you’re comparing like with like.

Roles are not personas but they shape motivations and constraints. Mixing roles too early almost always blurs the details that make personas meaningful. So start by looking at each role in isolation, for example:

-

How do support agents differ from marketers?

-

How do novice listeners differ from power listeners?

-

What pressures, workflows, or goals are unique to each role?

Only then look for consistent motivations, attitudes, and decision-making behaviors. I’ve found that using a structured synthesis method helps you avoid bias and see patterns you’d miss.

So here are two methods that work especially well:

-

Use an empathy map to cluster observations: This helps you organize everything people said, thought, did, and felt during your interviews. This is usually where persona “shapes” start to form naturally, because you’re grounding insights in observed behavior patterns.

-

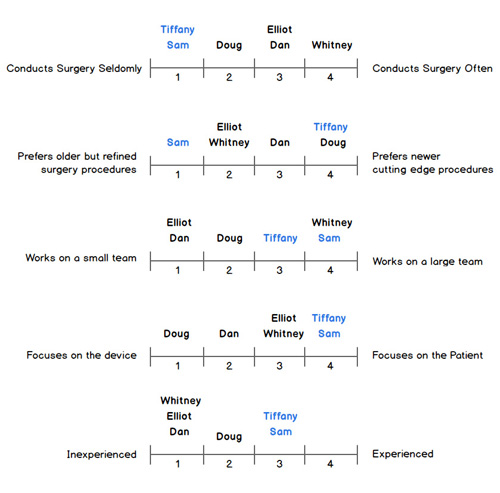

Score behaviors on a four-point spectrum to form clusters: Another way to structure your synthesis is to turn key attitudes and behaviors into discrete variables. Pick 5–20 that differentiate users like motivation strength, tech comfort, decision speed, goal orientation, etc. Then score each participant on a 1–4 scale. The four levels force you to choose a direction, reducing bias and preventing neutral scoring. Once plotted, you’ll notice small clusters of participants who align across most variables. Each cluster represents a distinct pattern of behavior, which becomes a persona.

4. Mould your insights into ideal customer personas

As the patterns are ready, the next step is turning those insights into concise, decision-ready personas.

The goal is to capture the dominant traits that genuinely influence how each group uses your product. That means focusing on a few key attributes (goals, behaviors, motivations) that clearly define each persona’s mindset.

A core part of building these personas is working out the behavior patterns to define their end goals. Questions included in the template below can be helpful for this process.

For example, Spotify’s research showed that some users primarily want to connect with others who share their music taste, share songs directly, chat in the app, and build collaborative playlists.

From those insights, they crafted a persona named Shannon Evans, a music-obsessed millennial tastemaker who loves collaboration and sees music as a way to bond with others.

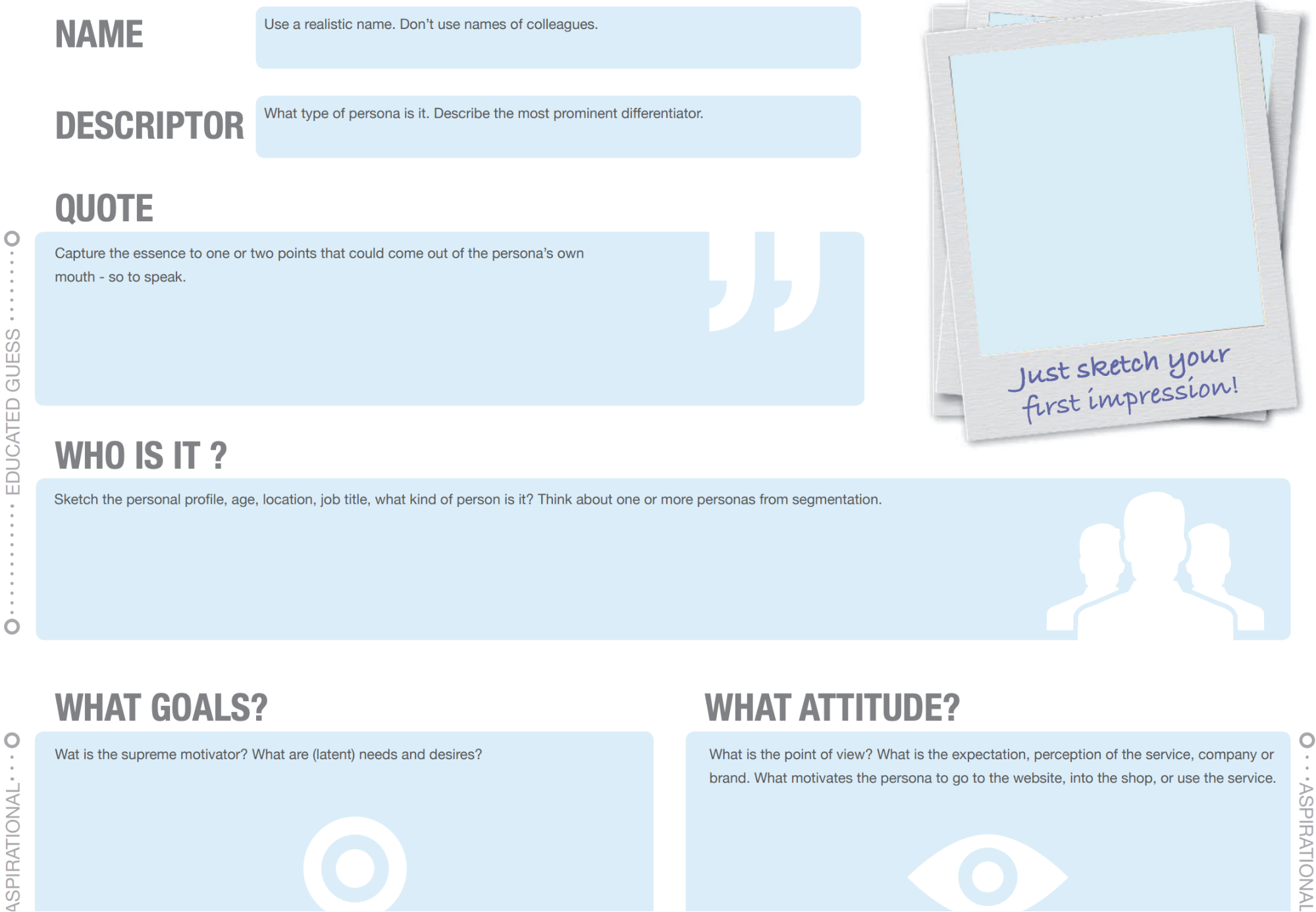

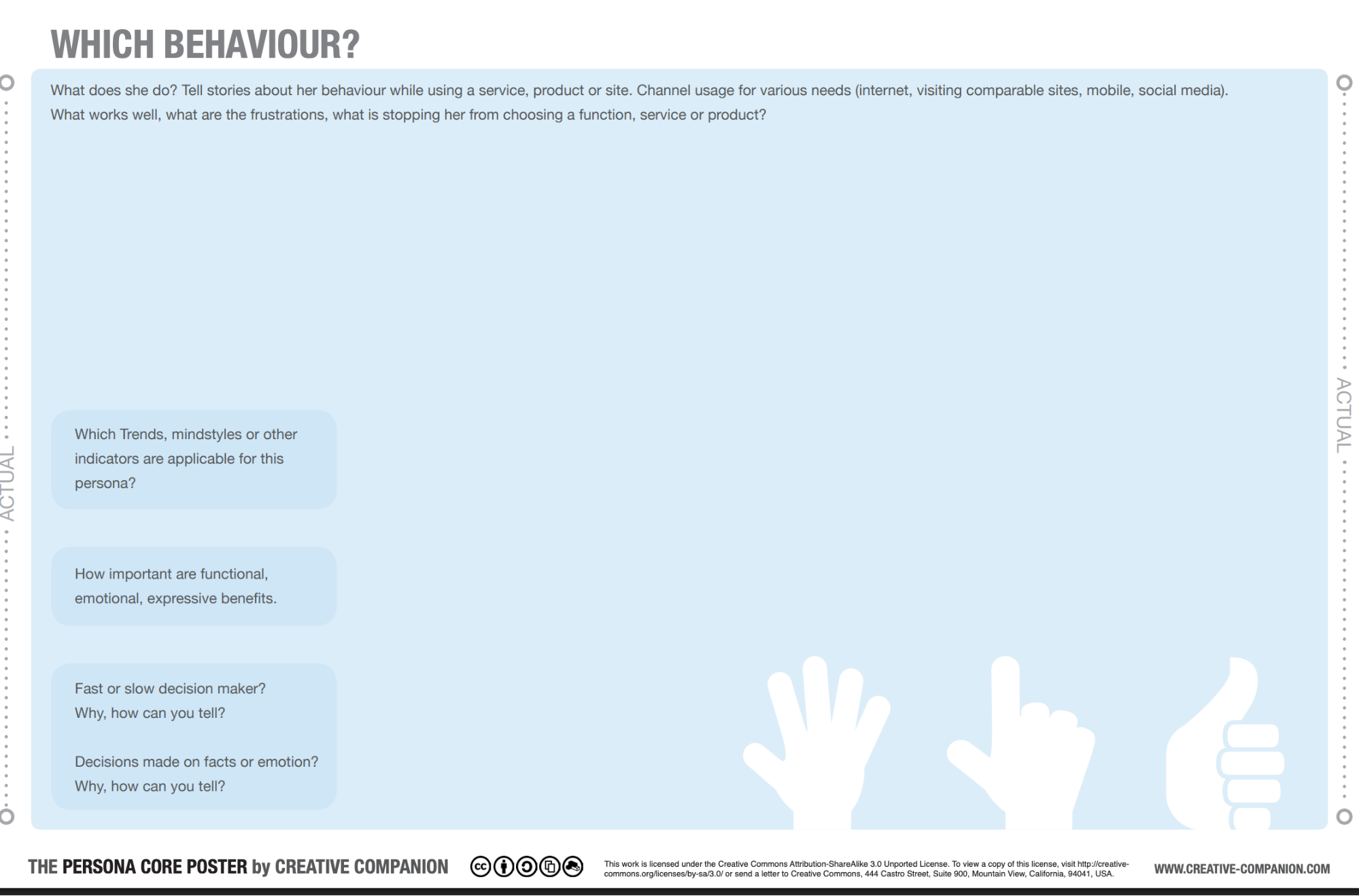

When you build personas, you can use user persona templates like the Persona Core Poster from The Persona Workshop. That poster forces you to boil things down to the essentials: a name, a quote, the user’s key attitude, their main goals, and their most representative behaviors.

5. Produce and adopt the persona

When you're done with the primary persona, you should use it to frame the design problem, prioritize features, and evaluate trade-offs.

A practical way for me to keep personas useful is to create a lightweight, consistent format. In most cases, you only need six elements to make a persona actionable:

-

name + descriptive title

-

demographic snapshot

-

quote

-

motivations and pain points

-

day-in-the-life narrative

-

end user persona goals

If you look at effective persona docs across well-known companies, two components always show up: Key Goals and Day in the Life.

Goals tell you what the user is trying to accomplish; the day-in-the-life gives you context for how your product fits into their routine. When these two are clear, everything else, including structure, flows, and feature priorities, becomes easier to reason about.

I’d also encourage adding two optional elements when useful: pain points and design imperatives. Pain points clarify what frustrates the user today, while design imperatives act as guardrails.

I feel like most teams stop here, but the last step is just as important: iterating. Personas should evolve as your customer base shifts, your positioning changes, or new behavior patterns emerge. I usually revisit them during major product updates or when the company enters a new segment.

7 types of UX personas

Not all personas are created equal, as different goals call for different kinds of user archetypes.

In this section, I’ll walk you through 7 persona types. explain how they differ, and help you decide which ones are right for products across different stages.

User persona example

A user persona represents the people who actively interact with your product day-to-day.

For SaaS and apps, this persona type helps you understand real usage patterns. This includes which features people rely on, where they get stuck, and what motivates them to keep coming back.

If your product’s success hinges on engagement and retention, this is the persona you should focus on.

Here's an example:

-

Basic demographics: Maya Lopez — 29-year-old marketing coordinator who runs 6–8 campaigns per month and uses your tool daily to manage workflows.

-

Goals and objectives: Reduce weekly reporting time by 30% and automate at least 40% of repetitive campaign tasks within the next quarter.

-

Challenges: Struggles to navigate cluttered dashboards and spends 20+ minutes locating performance insights needed for manager updates.

Buyer persona example

A buyer persona represents the people who purchase your product, not necessarily the ones who use it daily.

In B2B, this persona type is crucial because these individuals control budgets, evaluate competing solutions, and justify decisions to leadership.

If your goal is to improve win rates, shorten sales cycles, or strengthen enterprise positioning, this is the persona to map deeply.

Here's an example:

-

Basic demographics: Daniel Hart — 42-year-old VP of Operations at a mid-market logistics firm overseeing a team of 120 and an annual tech budget of $2.5M.

-

Goals and objectives: Reduce operational costs by 15% within 12 months and expand automation across 5 key workflows before the next fiscal cycle.

-

Information sources: Relies on quarterly industry benchmark reports, private leadership roundtables, and insights from a 3-person advisory council made up of former COOs.

Customer persona example

Customer personas represent the clients who already use your product and have measurable potential for renewal or expansion.

You should create this persona to understand what keeps them engaged, what blocks full adoption, and where opportunities for upsell or deeper product usage exist.

It’s most valuable for teams focused on retention, account growth, and long-term customer health.

Here's an example:

-

Profile: Marcus Hill — 42-year-old COO of a logistics startup generating $22M ARR, overseeing operations across three regions.

-

Goals and objectives: Reduce delivery errors by 15% in the next six months and automate manual reporting to save 10–12 hours/week for his ops team.

-

Adoption barriers: Struggles with fragmented data across four legacy systems, leading to incomplete dashboards; relies on an overstretched two-person IT team who slow down full product adoption.

Proto persona example

A proto persona is a fictional character and assumption-based profile you create before you have any research data. You use this type when you’re exploring a new market segment, evaluating early demand, or checking whether a new offering even deserves investment.

The goal is to make your assumptions explicit so you can validate or reject them quickly.

Here's an example:

-

Profile: Emily Carter — Operations manager at a 20–30 person DTC startup. Tech-forward, process-oriented, and constantly looking for tools that reduce manual workload.

-

Motivations: Wants to automate repetitive workflows and cut team time spent on coordination by 20–30%. Needs a tool that integrates seamlessly with existing stack (Slack, Notion, Shopify).

-

Frictions: Drowning in ad-hoc processes, scattered spreadsheets, and duplicate work created by siloed tools. Feels blocked by the lack of clear visibility into who’s doing what.

-

Current workarounds: Relies on messy Notion pages, manual Slack updates, and a patchwork of lightweight automations (Zapier, Make) that frequently break and require troubleshooting.

Marketing persona example

An audience persona represents a scalable marketing segment built from aggregated behavioral data, not interviews.

SaaS marketing teams often use this persona type to refine targeting, personalize campaigns, and optimize paid spend across channels.

It’s especially useful when you need clear patterns at scale rather than individual motivations.

Here's an example:

-

Segment overview: Gina Morales — Mid-level marketing manager at a fast-growing B2B company. Busy, ambitious, and constantly multitasking across channels.

-

Goals and bjectives: Aims to move from manager to director in 18 months by improving her strategic skills and delivering higher-impact campaigns with less manual effort.

-

Information consumption: Prefers fast, efficient formats e.g. watches YouTube tutorials at 2x speed, listens to marketing podcasts while at the gym, and saves TikTok tips during breaks between meetings.

-

Key signals: Engages with content on leadership, campaign automation, and analytics; clicks on case studies over long-form thought leadership; responds best to practical, time-saving insights.

Candidate persona example

A candidate persona represents the ideal job seeker your company wants to attract. HR and talent teams use this persona to shape job descriptions, employer branding, outreach messaging, and interview processes.

This persona helps clarify what motivates high performers and what barriers prevent them from applying.

Here's an example:

-

Profile: Marcus Lee — Senior Software Engineer seeking a transition into product. Ambitious, analytical, and drawn to companies that value internal mobility and cross-functional collaboration.

-

Goals and objectives: Wants to move into a Product Manager role within 6 months and increase total compensation by 20–30%. Ideally, through a mix of salary and equity.

-

Challenges: Struggles to stand out against candidates with MBAs or formal PM experience. Finds it difficult to translate engineering accomplishments into product-focused outcomes.

-

Key decision criteria: Looks for companies that offer mentorship from senior PMs, structured career-transition paths, and clear ownership.

Key takeaways

Most personas fail because you build them on assumptions instead of actual behavior. I've seen this happen at companies of all sizes. You skip the research, rush to create profiles, and then wonder why nobody uses them. Therefore, always make sure:

-

Ground everything in behavior, not demographics. You're tempted to focus on age or job title but that's surface-level stuff. What matters is how the persona act, what drives his decisions, and why he chooses one product over another.

-

Start with your hardest user. You don't need multiple personas early on. Pick the user who's most frustrated and design specifically for them. You can start with the rest when you have more data.

-

Make personas actionable, not decorative. You either use them in decisions or you don't. If they're not shaping your roadmap, they are useless to build.